Invading Malaya on 8th December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Army made swift advance south along the peninsula and then across the narrow strait into the supposedly impregnable fortress of Singapore.

Although numerically smaller military (35,000 Japanese to 85,000 Allies), the invaders dominated the air and the sea, allowing them to advance at will. By the time the Allied commands realised their impossible situation it was almost too late to evacuate non-combatants, let alone soldiers (Singapore fell on 15th February 1942). With news of Japanese inhuman and criminal treatment of women captives being heralded, General Bennett of the 2nd A I F finally relented and ordered the 130 nurses, all women under forty years of age, to be evacuated.

The Wah Sui, a hospital ship, was to take six nurses during the night of 10th February to safety, the Empress Star a further 59 on the morning of the 12th and the SS Vyner Brooke the last 65 during the night of the 12th. The nurses themselves did not want to abandon their patients.

The Wah Sui and Empress Star both made it through to Batavia in the Dutch Netherlands East Indies (which is now Jakarta, Indonesia), and then on to Australia.

The Vyner Brooke, not so lucky.

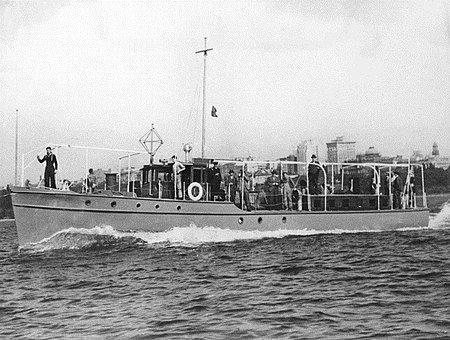

The SS Vyner Brooke was a Scottish-built steamship. She was 73.4m (240.7ft) long, with a beam of 12.6m (41.3ft) and draught of 4.95m (16ft 2 3⁄4in). At the outbreak of war with Japan the ship was requisitioned by the ROYAL NAVY, painted grey, and armed with a 25.4mm (four-inch) gun mounted on her forward deck, two x Lewis machine-guns mounted aft, aft and depth charges.

The ship was equipped with wireless and carried lifeboats, rafts and lifebelts for 650 people and could carry at least 200 deck passengers.

The ship’s Australian and British officers were mostly Malay Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve and had been asked to remain aboard the now HMS Vyner Brooke. The ship’s company, under the command of her peacetime captain, Richard E Borton, was augmented by Reservists, some being survivors of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, as well as some European and Malay sailors.

The Final Voyage

Tasked with evacuating nurses, civilians, and wounded servicemen from Singapore, the Vyner Brooke steamed out of Singapore Harbour on 12th February 1942, just three days before the garrison surrendered. The exact numbers of passengers are not known as records were incomplete and no longer exist. It is known that the crew numbered 40, there were 65 Australian Nurses, and approximately 145 others, including women and children.

Anchoring during daylight in the lee of islands to Singapore’s south to avoid discovery, she made slow progress.

At 9:00 AM on 14th February 1942, as she approached the Bangka Strait, the Vyner Brooke was sighted, bombed and strafed by nine Japanese aircraft. A bomb landed to the rear of the bridge, going deep into the ship before exploding. Another went down the funnel and destroyed the engine room. A third bomb exploded in the sea beside the starboard side, causing a great hole in the ship’s hull. She rolled onto her starboard side and sank within twenty minutes.

The SS Vyner Brooke was one of 40 ships sunk by Japanese aircraft approaching the Bangka Strait that day alone.

A further five ships made it through.

Four of the six life-boats were launched however, they immediately began filling with water from bullet and shrapnel holes received during the attacks. Ample life-rafts were successfully lowered for survivors. All passengers and crew had life-vests.

Most of the survivors reached Bangka Island, north of Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies; some within a few hours and some after three days afloat, such was the current.

Sadly, half-a-dozen were carried out to sea.

The Nurses

Sixty-five members of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), of the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (Malacca, Malaya), 2/13th Australian General Hospital (Tampoi, Johor, Malaya) and 2/4th Australian Casualty Clearing Station (Kajang, Malaya), were aboard the Vyner Brooke. They had already been through the mayhem of the Japanese advance and evacuations since 8th December 1941. They had withdrawn from Malaya to Singapore to the Anglo-Chinese School, St Patrick’s School and The Swiss Club, respectively, and then suffered the bombings and deprivations of battle there

Twelve lost their lives either during the bombing of the ship or in the water during more than 24 hours. All the survivors spoke of the extremely strong current and, where possible, they tied their life-rafts together so as to stay together. The six nurses whose life-rafts never made land had done exactly that. Their number also included some civilians and children.

Although seen by other survivors, they were unable to be reached and, it is assumed, washed out to sea with their bodies never recovered:

Twenty-two (22) Nurses, mostly from the two life-boats launched from the port side but also some on individual life-rafts landed on Radji Beach within hours of the sinking.

It was these who had lit a bonfire on the beach that was seen by many survivors in the water, however, unable to approach the beach due to the currents. The small group were joined by other survivors over the next twenty-four hours.

Then the Japanese Soldiers arrived, where they forced the Australian Nurses and a civilian woman to walk line abreast into the sea.

The women were struck from behind with machine gun fire and fell, one by one. Only Nurse and South Australian born Sister Vivian Bullwinkel survived; the bullet had passed through her body but missing her vital organs. Stunned, she lay in the shallow water next to the mutilated Nurses, with the waves washing over her, pretending to be dead until the Japanese soldiers departed.

The men who had landed on the beach, both military and civilian, were earlier slain nearby in two groups, the first bayoneted and the second shot.

The wounded on their stretchers were the last to be executed, by bayonet where they lay.

THIS EVENT BECAME KNOWN AS THE BANKA ISLAND MASSACRE

Those Australian nurses who landed and surrendered in other parts of the island and were taken to the tin smeltering town of Muntok. Whilst fortunate not to also have been brutally slain, they spent their next three-and-a-half years as POWs of the Japanese. Muntok’s timber and corrugated-iron cinema hall, built for 200 seated movie-goers, was overflowing with some 1,000 internees by sunset on the 16th.

The following morning all were marched out to the coolie camp on the outskirts of the town, a stone-walled set of huts previously used by Chinese labourers in the local tin industry. Here there was a well offering brackish water, but no baths or showers. A small hospital hut was cleaned-up and staffed, albeit with no medicines. The oldest of the Nurses were Nesta James (5 Dec 1903) and Eileen Short (15 Jan 1904), both 38 years of age. Nesta (2/10th AGH) was also the senior nurse. The youngest, at 25yo, were Joyce Tweddell (3 Jul 1916) and Wilma Oram (17 Aug 1916):

On 2nd March, the Nurses were given an hour’s notice that they were being moved: across Bangka Strait, to the city of Palembang, Sumatra.

They were housed in two typically-Dutch colonial homes; one occupied by the 2/13th AGH nurses (13 POWs) and the other by those of 2/10th AGH and 2/4th CCS (18 POWs). Jean Ashton and ‘Mitz’ Mittelheuser were elected ‘house captains’, respectively.

The Japanese refused to recognise the Nurses as prisoners-of-war, but rather as ‘internees’. A subtle difference maybe, but the Japanese government provided a token payment to POW’s, whereas ‘internees’ had to find work that brought a return!

Mid-way through 1944, the nearby men’s camp was moved and the women were re-located into one of the dormitories.

In October, however, the Japanese guards decided to again move the women. An initial party was despatched back to Bangka Island, but further inland than the ‘coolie camp’. Fairly new, and more space than the previous camps, this camp was surrounded by high bamboo fences. There was a hospital hut, a kitchen, a well with reasonable water, but no electricity. It was to accommodate some 550 women and 150 children.

The remainder of the nurses followed several weeks later.

Malaria, not a large problem until now, became acute by early 1945. By February, 31 of the 32 Australian Nurses were suffering from it. They called it ‘Bangka Fever’. Four of the Nurses succumbed to disease and malnutrition at Belalau on Bangka Island: Mina Raymont, ‘Rene’ Singleton, Blanche Hempsted and Dora Gardam.

In May 1945, the women’s camp was again moved, back to Sumatra, but to a rubber plantation about fifteen kilometres from Loebok Linggau. Starved of information of the outside world, the captives did not know that Germany had just surrendered.

Gladys Hughes died shortly after the re-location. Winnie Davis did likewise in mid-July. On 8th August, Dot Freeman and Pearl ‘Mitz’ Mittelheuser died on 18th August; three days after Japan’s surrender. The following day, the camp commander distributed Red Cross parcels he had been hoarding; no-one had needed to die of starvation!

Aftermath

The trauma caused by the announcement of the end of the war is often underestimated. The emotions of survival were immense. But, did anybody know where they were? How were they to be rescued?

By early September a small team of Dutch commandos, with radio communications to Ceylon, parachuted into the camp. There were still more armed Japanese guards than returning Dutch or other Allied troops to disarm and control them. Sporadic fighting started between Indonesian nationalists and the colonial Dutch troops. An Australian doctor, Major Harry Windsor, and the matron-in-chief of AANS, Colonel Annie Sage RRC, headed an Australian team in Singapore who were searching for the Vyner Brooke survivors.

Of course, they were searching for sixty-five (65) Nurses. Just sixteen remained and none weighed more than thirty (30) kilograms; so they were very feeble.

At 06:00 on 11th September the twenty-four Australian Nurses left Belalau as part of a larger group of sixty by two trucks (with two Australian para-troops) to the railway at Loebok Linggau, where they were put on a train to an airstrip at Lahat. From there an aircraft, with Doctor Harry Windsor (years later at St Vincent’s Hospital, Harry would perform Australia’s first heart transplant and mentored Doctor Victor Chang), flew them to Singapore. Iole Harper had discharged herself from the hospital. Jenny Greer was carried. And, they caught up on war news (they had only been told that the war was over; now they found out that the Allies had won), political developments (they never knew Curtin had replaced Menzies and had since died), fashions, films and music.

Windsor brought their enlistment photos for identification; the photos no longer matched the people!

Also aboard were Annie Sage, who addressed herself to the Nurses as your mother, and Nurse Jean Floyd, an original member of the 2/10th and then of the 2/13th who had been evacuated on the Empress Star Family.

At Singapore, they were admitted to the hospital (now the 2/14th AGH) at St Patrick’s School. Then, Nurse (Lieutenant) Vivian Bullwinkel was able to tell of the terrible massacre. Captain Orita Masaru of the 229th Regiment of the Imperial Japanese Army’s 38th Division became a prisoner of war of the Soviet Union following Japan’s surrender. After being held for three years, he was returned to Japan where he was charged with his war crimes.

On the eve of his trial, he committed suicide.

As a group, the 24 nurses boarded the Manunda on 5th October for home. Their numbers depleted as the ship made port at Fremantle (Western Australia), Port Melbourne (Victoria) and Sydney Harbour (New South Wales).

Back in Australia, after being feted at official receptions, they were each granted a month’s leave to consider their futures, and then individually de-mobilised between 9th January 1946 (Cecilia ‘Del’ Delforce) and 10th October 1948 (Ada Syer).

The last to finalise her military service was Vivian Bullwinkel. Vivian served in the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan in 1946 and 47, during which time, being an eyewitness, she gave evidence at the Tokyo war crimes tribunal, before being de-mobilisation from the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).

She transferred to the militia, remaining until 1970 and retiring as a Lieutenant Colonel. She was awarded the Associate Royal Red Cross (ARRC) and Florence Nightingale Medal in 1947, and later appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in 1973 and Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 1993

Top: Captain Vivian Bullwinkle Testifying at the War Crimes Tribunal in Tokyo

Left: Sister Vivian Bullwinkle before transferring for service in Malaya

Seven of the survivors returned to Bangka Island in 1993 for the dedication of a Memorial: Jennie Ashton, Vivian Bullwinkel, Pat Darling (nee Gunther), Mavis Allgrove (nee Hannah), Wilma Oram, Flo Syer (nee Trotter) and Joyce Tweddell.

Pat Darling (nee Gunther) passed away in December 2007, aged 94 years.

She was the last of the Vyner Brooke Nurses.

During the Second World War, 3,477 women joined the AANS. This story is about just 65 of them. However, of 71 members who lost their lives during the war, 41 were from the Vyner Brooke.

Thirty-eight AANS members became prisoners-of-war, with 24 of those from the Vyner Brooke.

Of 137 decorations awarded to AANS members, sixteen were associated with this single incident. The Vyner Brooke group were certainly significant in the life of the AANS.

Honors & Awards

For exceptional services in military nursing, the Royal Red Cross First Class (RRC) was awarded to Olive Paschke. Associate, or Second Class (ARRC), crosses were awarded to Jessie Blanch, Vivian Bullwinkel and Nesta James.

Awarded to ladies who have made an outstanding contribution to the nursing profession, the Florence Nightingale Medal was awarded to Vivian Bullwinkel ARRC.

Mention in Despatches, in Australia now the Commendation for Gallantry, was awarded to Jean Ashton, Cecilia Delforce, Irene Drummond, Jess Doyle, ‘Pat’ Gunther, Nesta James ARRC, Chris Oxley, Jessie Simons, Val Smith, Ada Syer and Flo Trotter.

Most of the nurses also qualified for the 1939-45 Star, Pacific Star, War Medal and Australian Service Medal 1939-1945.

Some qualified for the Defence Medal.

Ladies – Thank you for your service and sacrifice.

Written and spoken by: Ron S Read RAN (Rtd) – Copyright 2024.