Sometimes called “The Forgotten War”

Just five years after the conclusion of the Second World War, Australia became involved in the Korean War. Personnel from the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), and the Australian Regular Army (ARA) were committed soon after the war began and would serve for the next three years in the defence of South Korea.

Prelude to war:

The origins of the Korean War can be traced back to the end of the Second World War, when the Allies were entrusted with control of the Korean peninsula following 35 years of Japanese occupation. The United States and the Soviet Union accepted mutual responsibility for the country, with the Soviets taking control of the country to the north of the 38th Parallel and the United States taking the south. Over the next few years, the Soviet Union fostered a communist government under Kim Il-Sung and the US supported the provisional government in the South, headed by Syngman Rhee. By 1950 tensions between the two zones had risen to the point that two increasingly hostile armies had built up along the 38th Parallel.

In the pre-dawn hours of June 25, 1950, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) launched a massive offensive across the 38th Parallel into South Korea. They drove the Republic of South Korea’s (ROK) forces down the peninsula, capturing the capital, Seoul, within a week. South Korean and hastily deployed United States Army units fought delaying actions as they were forced further down the Korean peninsula, which allowed defensive positions to be set up around the port city of Pusan.

Australia commits:

Within two days of the war’s beginning, US President Harry S. Truman committed US Navy and Air-Force units to aid South Korea. By the end of the month, he had authorised US ground forces to be deployed to the peninsula.

The United Nations Security Council asked its members to assist in repelling the North Korean invasion. The Security Council was aided by Russia boycotting the UN over its lack of recognition of the communist Chinese government. With the Russian delegate absent and unable to veto any resolution, the UN was able to act decisively and commit forces from willing nations to the aid of South Korea. In all, 21 nations committed troops, ships, aircraft, and medical units to the defence of South Korea. Australia became the second nation, behind the United States, to commit personnel from all three of our armed services to the war.

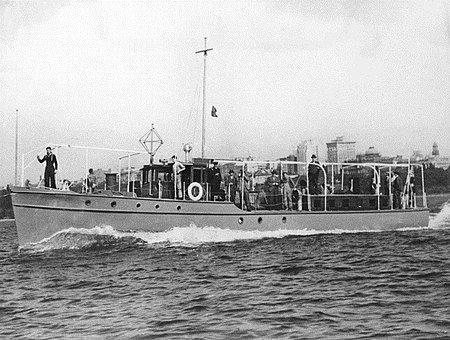

Australia, with its commitment to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan, had two readily deployable RAN vessels, HMAS Shoalhaven and HMAS Bataan (which was on its way to Japan to relieve Shoalhaven), as well as No. 77 Squadron, RAAF.

The 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR) was also available, but it was under-strength and ill-prepared for a combat deployment.

On 28 June Prime Minister Robert Menzies committed Australian NAVY assets to the Korean War, followed several days later by the RAAF No. 77 Squadron.

It wasn’t until 26 July that 3RAR was committed to ground operations in Korea.

The Royal Australian Navy during the course of the war played a major part, with nine (9) ships on station at various times, include our air-craft carrier HMAS Sydney with 3 x Fleet-Air-Arm squadrons embarked, PLUS the Battle Class Destroyers – HMAS Bataan, Warramunga, Anzac and Tobruk

and the British designed but built in Australia Bay Class Frigates – HMAS Murchison, Shoalhaven, Condamine and Culgoa.

First to fight:

On 1 July HMAS Bataan and HMAS Shoalhaven left Japanese waters escorting US troop ships to Pusan. The following day, No. 77 Squadron, led by Wing Commander Lou Spence, flew the first ground support operations over Korea, becoming the first British Commonwealth and United Nations unit to see action in the Korean War. Over the next few weeks, No. 77 Squadron flew numerous sorties against KPA forces and, along with other allied air units, greatly assisted in slowing the North Koreans’ advance.

3 RAR (Royal Australian Regiment) deploys:

In mid-July General Douglas MacArthur was appointed Supreme Commander of United Nations forces in Korea and wasted no time in requesting the deployment of 3RAR to the peninsula. The Australian government agreed, but stipulated that the battalion would deploy only when fully ready. The battalion was brought up to strength over the next month and a half with reinforcements from K Force, an Australian government initiative calling for volunteers to serve a three-year period in the army, including a year in Korea. In early September, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Green took command of the battalion and put his men through an intensive training program.

In a brilliant master stroke, General MacArthur landed marines of the 1st Marine Division at Inchon on 15 September. Two days later, ROK, US, and British troops took part in the breakout from the Pusan perimeter. One week later, Seoul had been recaptured and UN units began their advance towards the North Korean border. On 27 September 3RAR embarked from Kure in Japan, and arrived at Pusan the following morning. The Australian battalion was taken on strength of the British 27th Brigade, joining the 1st Battalion, Argyll and Southerland Highlanders, and 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment. The brigade was renamed the 27th Commonwealth Brigade to reflect its Antipodean addition.

3RAR’s first battle

As UN forces neared the North Korean border, China warned them not to cross into North Korean territory, and that such an incursion would not be tolerated. General MacArthur received permission to pursue the fleeing North Korean forces and shortly after crossed into North Korea. The capital, Pyongyang, fell soon after.

As part of the 27th Commonwealth Brigade 3RAR advanced north of Pyongyang to assist the US 187th Regimental Combat Team, which had encountered heavy resistance after being dropped behind enemy lines in an attempt to rescue American prisoners of war. On the morning of 22 October 1950, 3RAR was the lead battalion leaving the town of Yongju when it came under fire from enemy troops within a nearby apple orchard. The ensuing fight was swift and brutal, with the Australians routing a numerically superior force and suffering only seven wounded. It was the first combat action fought by a battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment and the men of 3RAR had acquitted themselves well. In the following week those men would fight two more battles – at Kujin, known as the battle of the broken bridge, and Chongju.

At the beginning of November, 3RAR’s commanding officer, the indomitable Lieutenant Colonel Charles Green DSO, was mortally wounded by shrapnel as he rested in his tent. Several North Korean artillery rounds had been fired into 3RAR’s position but Green was the only casualty. He died of his wounds two days later.

China enters the war

The battle of Pakchon marked the furthest point that the Australians reached into North Korea. It was also the first time Chinese forces were encountered in large numbers. Unbeknownst to UN intelligence sources, Chinese troops had been infiltrating North Korea across the Yalu River, and in late October they began an offensive against, annihilating several UN divisions and badly mauling others before seeming to melt away. The ensuing weeks saw an eerie quiet settle over the battlefield.

In November, buoyed with a false sense of security, UN forces under MacArthur’s direction once again began to advance north towards the Yalu River. On 25 November the Chinese launched the next phase of their offensive and by January 1951 had pushed the UN forces back across the 38th Parallel.

During the retreat, the 27th Commonwealth Brigade had fought many rear-guard actions, allowing formations from the US and South Korea to pass through their positions. The brigade was the last formation out of Seoul before the city once again fell to Communist forces in January 1951.

At the UN headquarters in New York ceasefire negotiations between the UN and the Communist coalition broke down before any real progress could be made.

The Chinese sought to renew their advance in February, but were halted and forced to retreat by UN troops. Seoul was recaptured by UN forces in March and the Chinese were pushed back towards the 38th Parallel. Opinions were divided amongst the UN commanders whether to pursue Chinese forces across the 38th Parallel or to push for a ceasefire at the border. General MacArthur pushed for the advance to continue and on 11 April 1951 he was relieved of command by President Truman.

A new war-horse No. 77 Squadron, RAAF, flew their last operations in Mustangs in early April, after which they returned to Japan to begin conversion to the Gloster Meteor F8. Four RAF pilots had been sent to Japan to train the Australians and were taken on strength of the squadron. In all, 37 RAF pilots would fly on operations with the squadron, six of whom were killed and another of whom was shot down and taken prisoner. The squadron returned to combat operations in July and after some disastrous air-to-air battles with MiGs the squadron reverted to its former role of ground attack, carrying out many successful operations during the next two years.

Kapyong

On 22 April, the Chinese launched their spring offensive, routing the South Korean 6th Division and driving them back down the Kapyong Valley. The 27th Commonwealth Brigade advanced forward of the town of Kapyong. The 1st Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, and 3RAR dug in on the high ground on either side of a seven kilometre wide valley. The following day, the Chinese were engaged by the Australians and Canadians as well as a troops of US Army Sherman tanks and New Zealand Artillery. Two nights and days of close fighting followed and on the evening of 24 April the Australians were forced to withdraw from their positions and, with the support of the Canadians and New Zealand artillery, fought their way down a ridge, rejoining the majority of the brigade in the Kapyong valley. The Chinese were stopped in their tracks and Seoul was saved from being attacked once more. The men of 3RAR suffered heavy casualties, with 32 killed, 53 wounded, and three taken prisoner.

Following the battle, the 27th Brigade was withdrawn from Korea and 3RAR was taken on strength of the 28th British Commonwealth Brigade, part of the newly formed 1st Commonwealth Division.

Negotiating the peace

On 10 July peace negotiations began between the warring powers in the town of Kaesong. Negotiations were suspended in August after the building used was reportedly bombed. Talks did not resume until October, and from then on were held in the village of Panmunjom.

Maryang San

On 3 October, as a part of Operation Commando, a large UN offensive against a Chinese salient, 3RAR advanced north of the Imjin River, attacking two key high points: hills 317 and 355. After five days of heavy fighting the Chinese were forced to withdraw off both objectives, and on repulsing several counter-attacks the men of 3RAR were firmly in control of Hill 355, known as Maryang San. The Australians suffered 20 men killed and a further 89 wounded during the fighting.

Air-craft carrier HMAS SYDNEYcommences operations

during the winter of 1952 in Korean waters

HMAS Sydney arrived in Korean waters in early October and began operations immediately. On board the carrier were three squadrons of the RAN Fleet-Air- Arm, No’s 805 and 808 squadrons, flying Hawker Sea Furies, and No. 817 Squadron, flying Fairey Firefly aircraft. The Sydney undertook numerous patrols in Korean waters during its deployment and its aircraft flew over 2,300 sorties, including ground attacks, artillery spotting, and escort missions.

It incurred the loss of three crew and 13 aircraft. HMAS Sydney returned to Australia in January of 1952.

Static war

Following the Chinese retaking of Maryang San in a bitter encounter with the Kings Own Scottish Borderers, the fighting became static. Trenches, tunnels, and redoubts reminiscent of the Western Front became the norm. Patrols and trench raids became commonplace, as did set-piece artillery battles.

In April 1952, 1RAR arrived in Korea and joined 3RAR as part of the 28th Brigade. During its service, 1RAR took part in many patrols of no-man’s land and several operations against Chinese positions. The Australians’ reputation for patrolling and raiding from both the First and Second World Wars was further enhanced by the efforts of the men of 1RAR and 3RAR during 1952. 1RAR was replaced by 2RAR in April 1953 and quickly established itself as a formidable patrolling and raiding force.

An armistice at last?

On 19 July an agreement for an armistice between the UN and the Communists was reached. The date for the signing was set for the 27th of July.

The Samichon

The last three days of the Korean War saw the Chinese mount one last offensive on Australian and US Marine positions in the Samichon Valley. The Chinese attacked in waves with heavy artillery support. However, the combined arms of the US and Commonwealth forces halted the Chinese attacks with heavy losses. This final battle cost 2RAR six killed and 24 wounded. The Marines suffered 43 killed and 316 wounded.

Is it really over?

The armistice was signed at 10 am on 27 July 1953. Sporadic fighting continued throughout the day, but as evening fell the guns fell silent.

The armistice came into effect at 10 pm, ending three years, one month, and two days of war in Korea. The end came so suddenly that some soldiers took some convincing that the fighting was really over.

The former belligerent nations each withdrew two kilometres in accordance with the armistice agreement, forming the Demilitarized Zone which still exists today.

Australian Forces remained in Korea as part of the multi-national peacekeeping force until 1957.

Over 17,000 Australians served during the Korean War, of which 340 were killed and over 1,216 wounded. A further 30 had become prisoners of war.